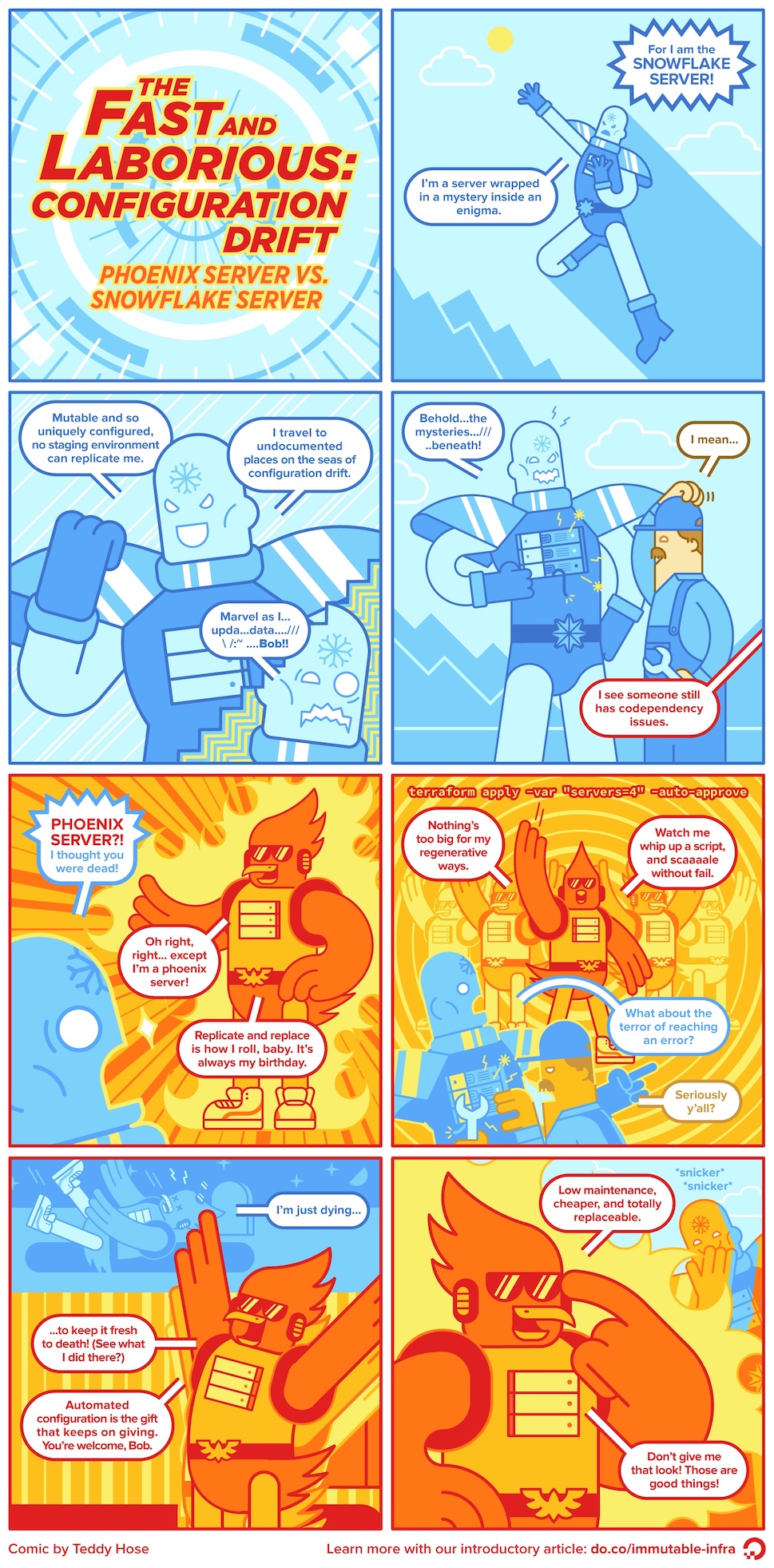

雪花服务器与凤凰服务器

Dec 1, 2020 20:30 · 1953 words · 4 minute read

译文

雪花服务器

维持一台生产服务器运行并非易事,首先你得保证操作系统和其他软件都被修补至最新,被托管的应用程序也要周期性地被升级,甚至需要定期更改配置来调整环境使其高效运行并且保证和其他系统的通讯正常。这就需要一堆命令行操作,在终端之间反复横跳,编辑文本文件啥的。

这就导致了服务器像一片独特的雪花与众不同——对数据中心来说不是什么好事。

雪花服务器第一个问题是难以复制。要是你的服务器挂了,很难另起一台服务器来支持相同的功能。如果你要一个集群,难以保证集群中所有的实例都是同步的。你也不能很轻易复制一个生产环境来测试,当业务出问题时,无法通过在开发环境中重现事务执行来排查故障。

也许给雪花服务器创建磁盘镜像会有所帮助。但这样的镜像乱七八糟,还有很多不必要的配置,更不用说其他错误了,都统统被一起打包。

然而雪花服务器真正的弱点,在于当你要更改它的时候,会越来越难以理解和修改,升级某个小软件可能会引发一串不可预知的连锁反应。你也不确定哪些配置是重要的,或者只是开箱就有的默认配置,这种脆弱性使人在调试的时候神经紧绷压力山大。你要手动操作的流程和文档来支持任何审计需求。这就是为什么你经常看到重要的软件在古老的操作系统上跑的原因之一。

避免雪花服务器的一个好办法是通过自动化运维来掌控所有配置。Puppet 和 Chef 最近非常流行,允许你使用 DSL 的形式来定义操作环境(而现在是 Ansible 和 SaltStack),将配置轻松应用至目标系统中。

使用它们的意义不仅在于你可以很轻松地重建服务器(当然也可以用镜像来重建),而且也可以很容易地了解那些配置,从而更容易地修改它们。此外,一般这些都是文本文件,可以纳入版本控制,这就是基础设施即代码。

如果你禁止直接 ssh 任何服务器,并强制从版本控制中运行“配方”来应用所有配置更改,这就有了一个很棒的审计机制,确保环境的每一个更改都会被记录下来。这个是正规路子。

应用程序部署要遵循相同的原则:完全自动化,所有更改纳入版本控制。通过避免雪花服务器,可以轻易地搞出与生产环境相同的测试环境,避免因配置误差导致额外的问题。

要成为“凤凰服务”而不是“雪花服务器”,使用版本控制的“配方”来定义服务器配置是持续交付很重要的一部分。

凤凰服务器

这个想法可能很蠢,但也有些许智慧的金块在闪光。定期“烧掉”你的服务器可能是个好主意,服务器应该像凤凰,能够从灰烬中重生。

凤凰服务器的优势在于避免配置乱漂:对系统配置的临时更改没被记录下来。漂着漂着就上了去雪花服务器的路(量变引起质变)。

对抗漂移的一种办法是使用软件,以已知的基线自动同步服务器。Puppet 和 Chef 这样的工具都有这个功能,自动重新应用定义好的配置。局限性在于像这样重新应用只能控制你定义好的区域,然而在这些区域外的就没用了。既然凤凰服务器是完全从“源码”开始孵化的,如果源头就有问题,上梁不正下梁自然歪。

这并不意味着重新应用配置没用,通常比“烧掉”服务器更快,破坏性更小,使用这种策略来避免服务器雪化还是有价值的。

原文

Snowflake Server

It can be finicky business to keep a production server running. You have to ensure the operating system and any other dependent software is properly patched to keep it up to date. Hosted applications need to be upgraded regularly. Configuration changes are regularly needed to tweak the environment so that it runs efficiently and communicates properly with other systems. This requires some mix of command-line invocations, jumping between GUI screens, and editing text files.

The result is a unique snowflake - good for a ski resort, bad for a data center.

The first problem with a snowflake server is that it’s difficult to reproduce. Should your hardware start having problems, this means that it’s difficult to fire up another server to support the same functions. If you need to run a cluster, you get difficulties keeping all of the instances of the cluster in sync. You can’t easily mirror your production environment for testing. When you get production faults, you can’t investigate them by reproducing the transaction execution in a development environment.

Making disk images of the snowflake can help to some extent with this. But such images easily gather cruft as unnecessary elements of the configuration, not to mention mistakes, perpetuate.

The true fragility of snowflakes, however, comes when you need to change them. Snowflakes soon become hard to understand and modify. Upgrades of one bit software cause unpredictable knock-on effects. You’re not sure what parts of the configuration are important, or just the way it came out of the box many years ago. Their fragility leads to long, stressful bouts of debugging. You need manual processes and documentation to support any audit requirements. This is one reason why you often see important software running on ancient operating systems.

A good way to avoid snowflakes is to hold the entire operating configuration of the server in some form of automated recipe. Two tools that have become very popular for this recently are Puppet and Chef. Both allow you to define the operating environment in a form of DomainSpecificLanguage, and easily apply it to a given system.

The point of using a recipe is not just that you can easily rebuild the server (which you could also do with imaging) but you can also easily understand its configuration and thus modify it more easily. Furthermore, since this configuration is a text file, you can keep it in version control with all the advantages that brings.

If you disable any direct shell access to the server and force all configuration changes to be applied by running the recipe from version control, you have an excellent audit mechanism that ensures every change to the environment is logged. This approach can be very welcome in regulated environments.

Application deployment should follow a similar approach: fully automated, all changes in version control. By avoiding snowflakes, it’s much easier to have test environments be true clones of production, reducing production bugs caused by configuration differences.

A good way of ensuring you are avoiding snowflakes is to use PhoenixServers. Using version-controlled recipes to define server configurations is an important part of Continuous Delivery.

Phoenix Server

This may be a daft fantasy, but there’s a nugget of wisdom here. While you should forego the baseball bats, it is a good idea to virtually burn down your servers at regular intervals. A server should be like a phoenix, regularly rising from the ashes.

The primary advantage of using phoenix servers is to avoid configuration drift: ad hoc changes to a systems configuration that go unrecorded. Drift is the name of a street that leads to SnowflakeServers, and you don’t want to go there without a big plough.

One way to combat drift is to use software that automatically re-syncs servers with a known baseline. Tools like Puppet and Chef have facilities to do this, automatically re-applying their defined configuration. The limitation is that re-applying configuration like this can only spot drift in areas that you’ve defined that the tools control. Configuration drift that occurs outside those areas doesn’t get fixed. Since phoenixes start from scratch, however, they will pick up any drift from the source configuration.

This doesn’t mean that re-applying configuration isn’t useful since it’s usually faster and less disruptive than burning down a server. But it’s valuable to use both strategies to fight away the snowflakes.